It was near my house

I worked for the INSCO Systems Corporation, aka Insco, for thirteen mostly happy years, the longest I ever worked in the same place.

Lots of things ‘happened’ there and this article was getting too long, so I decided to break it up into six easier-to-digest parts. This is Part 1. I’ll try to keep the technical stuff to a minimum; these are about people.

Writing about my previous employer, Hess Oil, I mentioned my cousin seeing a highway billboard advertising for computer programmers. I got one of those jobs, and it turned out to to be a pretty good one.

Some of the ‘happenings’ written about here might make the company look clueless at times, and one or two of its people mean-spirited, but that can be true in any bureaucracy. I enjoyed my years at Insco. I kept my head down, stayed out of office politics as much as possible, and have many fond memories.

Moving the work to New Jersey

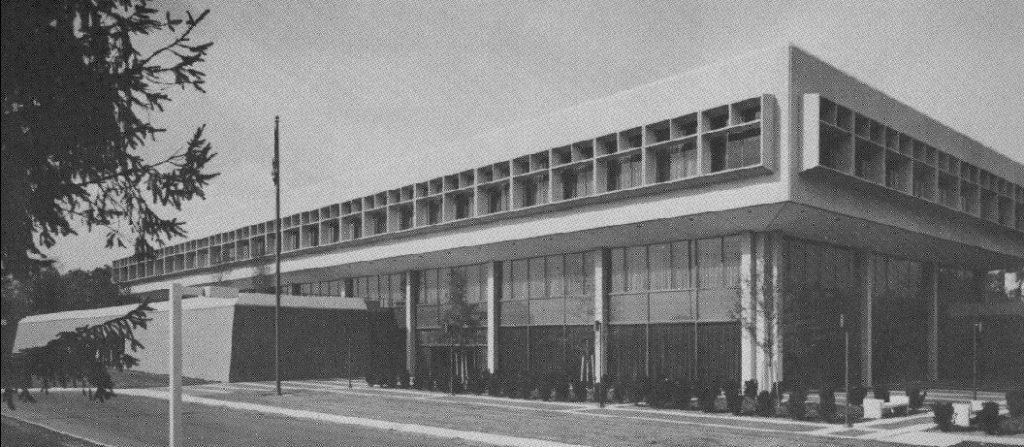

Continental Insurance was outgrowing its office in New York City, so they commissioned a three-story modern building in Neptune, New Jersey where they would relocate their data processing. Expecting a tax advantage, in 1968 they established the site as a separate company, naming it INSCO Systems. During the next tax season, they discovered there was no real advantage to having a separate company, and changed the name back to Continental. I’ll call it Insco here because that’s what the employees always called it.

Getting hired

I hate commuting; it’s a waste of time and money. Insco was only thirteen miles and one toll plaza away from my house, so even knowing nothing about the company, I was interested in working there. I sent them a resumé but I didn’t have expertise in the operating system they were using. I got a personal letter that thanked me for applying, said my resumé looked fine, but that one skill was lacking. A few weeks later they ran a newspaper ad; I answered it and got another nice letter, same skill still lacking.

After one more cycle of this, they realized they were not going to find that skill in Central Jersey. They designed a four-week training class, ran a new ad and contacted people like me that they’d been turning down.

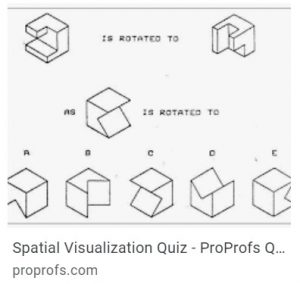

I came in, filled out an application and had the usual is-the-applicant-sane initial screening. Next, they gave me an IQ test (employers could do that then), then a “spatial reasoning” test, imagining rotations of 3-D objects. The 3-D puzzles were easy, and after a technical interview with a department head, in May of 1971 I was hired.

Starting work

They had already moved the mainframe computers from New York to Neptune, along with the programming staff who wanted to relocate. After the class, I was assigned to a development group and given the first of many assignments.

About two months later, I got a phone call asking me to come downstairs and see Bob Hoberman, the head of Personnel. Mr. Hoberman said he had heard good things about my work, but Orange High School couldn’t find any record of my graduating. I explained that I didn’t actually “graduate” graduate, but had taken the state high school equivalency tests a few years earlier, and had a GED certificate. He really wanted to help, and said “So, when you said on your application you graduated high school, that was a figure of speech?” I grabbed that phrase like a drowning man, and said he was correct. Thank you, Mr. Hoberman, you are a gentleman.

I never received the actual GED certificate in the mail, and asked my wife to help track it down. She talked to a nice woman in Trenton and found out I had juussssstt missed passing one of the five test sections, math. The woman went all-out, working with Mimi to identify any “life experience” that might get me some extra educational credit. Finally, she asked if I’d been in the military, and bingo, I had some life credits and a GED.

The company had two mainframe computers – a production one to collect data from branch offices around the country and handle insurance-policy production and claims, the other a VM system to support development and testing of the production programs. VM stands for Virtual Machine, and each VM user has their own separate and independent virtual computer, with exclusive access to an imaginary card reader, card punch, printer, and tape drive. It’s so clever it’s almost magic.

Application programmers wrote their programs with pencil on paper forms at their desks, got them punched into cards by the keypunch department, then used the terminal room workstations to test, modify and improve them.

“Talking to the metal”

After I’d been in applications development for about a year, an opening came up in the technical unit, the group that fed and tended the mainframe computers. I knew assembler language, which is how software “talks to the metal”, as the expression goes, so I had a leg up. I interviewed for the opening and was offered a transfer. Special thanks to vice president Phil Keating, who did not oppose my transfer out of his group, saying he wanted to have at least one friend in the technical unit.

Managing attendance

At some point, the company switched to flextime, a policy that respects employees’ need to sometimes conduct personal business such as medical appointments during work hours. Borrowing from Wikipedia,

Flextime allows workers to adjust their start and finish times as long as they complete the required daily/weekly number of hours. There is a “core” period during the day when all employees are required to be at work, and outside that a flexible period, within which all required hours must be worked.

I didn’t have any childcare issues or rely on public transportation, so to me flextime wasn’t that big a deal . But it did mean I could go for a run in the morning without starting out in the dark.

My boss’s boss, senior vice president Gordon Gilchrest, was old-school; he hated what he saw as the unpredictability of flextime. When we discussed the policy, he kept interrupting with “But when will you be here?”. I wanted to answer “Whenever the hell I feel like it, that’s the whole idea” but instead I just said I’d probably come in two hours later on Tuesdays and Thursdays. He wasn’t thrilled with that either, but at least it was predictable.

Tracking our hours

Right about the time flextime went into effect, the company bought, or had sold to it, the “Accumulator” system, with an Accumulator placed in each department, near the secretary’s desk. It was a little bigger than a hardback book, with maybe 20 slots on the front. Each employee had a card with their name on it sitting in one of the slots. Each card, or ‘plug’, was like a tiny odometer, clocking how long it was plugged firmly into its slot, meaning the employee was at work. When the employee was not at work, the plug was pulled out far enough to disengage, making a soft click and stopping the clock. At least that was the theory.

Side story: at 8:30 one morning, a supervisor saw two clerks from his department having a cafeteria chat with someone from another unit, and suspected they were clocked in and chatting on company time. Co-opting an unrelated figure of speech, he asked “Are you girls on the plug?”, to which they replied indignantly “NO WE’RE NOT ON THE PLUG.”

Humans, professionals in particular, don’t like punching a time clock, which is basically what the Accumulator was. Consciously or unconsciously, people forgot to push their plugs in or pull their plugs out as appropriate when they started work, went to lunch, or left for the day, making the system effectively worthless. Plugs were recording weekly attendance from zero hours to over 100.

Flextime became a permanent policy, but the Accumulators, rendered useless by human nature, were removed. There are no photos of the Accumulator out on the internet for me to show you, suggesting they never worked anywhere else either.

Paul was a young programmer and philosophy major who was taking a night course in statistics at Rutgers-Newark. As he started home one night, he was stopped by two locals who wanted his wallet and briefcase. He resisted, and they stabbed him to death. When I heard, I thought, one more crime that will never be solved. But while writing this I found out, via newspapers.com, that the two were identified by a witness, arrested, and in 1982 sentenced to life in prison. 1982 is a long time ago, but I hope “Life” means life, and they are still there. That’s why I pay taxes.

Paul was a young programmer and philosophy major who was taking a night course in statistics at Rutgers-Newark. As he started home one night, he was stopped by two locals who wanted his wallet and briefcase. He resisted, and they stabbed him to death. When I heard, I thought, one more crime that will never be solved. But while writing this I found out, via newspapers.com, that the two were identified by a witness, arrested, and in 1982 sentenced to life in prison. 1982 is a long time ago, but I hope “Life” means life, and they are still there. That’s why I pay taxes.