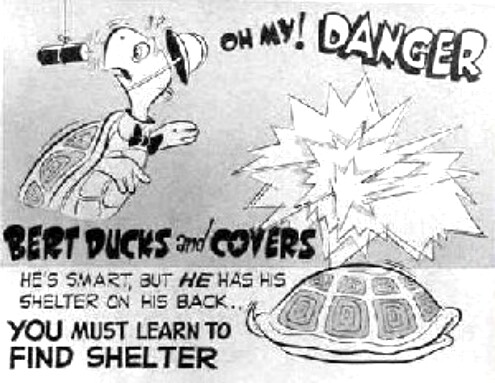

“The film starts with an animated sequence, showing a turtle walking down a road, while picking up a flower and smelling it. A chorus sings the Duck and Cover theme:

There was a turtle by the name of Bert

and Bert the turtle was very alert;

when danger threatened him he never got hurt

he knew just what to do …

He’d duck! [gasp]

And cover!

Duck! [gasp]

And cover!

(male) He did what we all must learn to do

(male) You (female) And you (male) And you (deeper male) And you!

[bang, gasp] Duck, and cover!“

I did not grow up with a “constant fear of nuclear attack by the Soviets”, and for that happy truth I thank the Orange, New Jersey school board, which made the curriculum decisions affecting me and my schoolmates. We did have some fear, but it wasn’t constant. I’d call it more of a low-grade background concern, and a condition of life in the 1950s and ’60s.

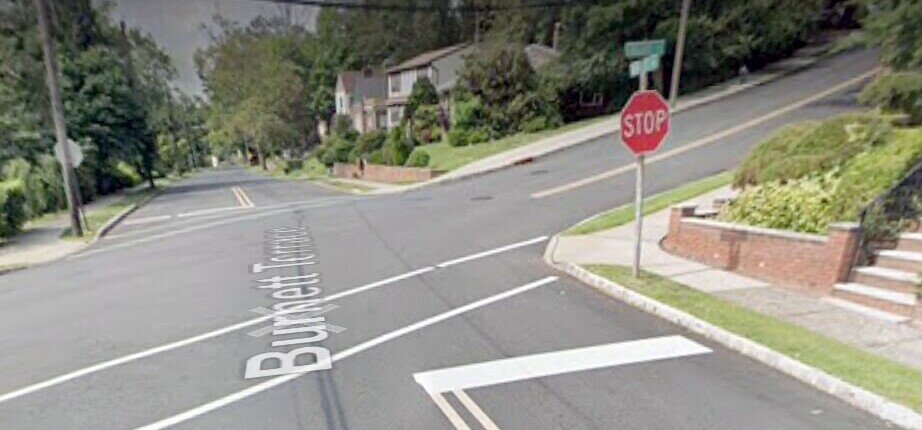

We had only one duck-and-cover drill at Cleveland Street School, in sixth grade. I don’t recall being shown the Duck and Cover film, or getting any advance explanation for the drill, but one morning we were taught how to crawl under our desks and curl up in a ball. Our classroom was partly below ground level, with the window sills level with the asphalt playground outside. We were told that when we saw the flash we should not look out the window under any circumstances, but instantly get under our desks, facing away from the windows, which would shatter inward in just a few seconds when the blast wave arrived. We should keep our eyes closed and curl up with clasped hands protecting our necks, tricky when your desk’s iron legs are bolted to the floor.

If we happened to be outside when we saw the flash, we should drop down next to a curbstone, or lie down next to a log (assuming the town’s pioneer settlers left some unused logs behind, which they had not).

We never discussed that drill – in class with the teacher, among ourselves, or with our parents. and we never had another one. I think someone on the school board decided they were pointless, stupid and frightening, and said let’s not do that any more.

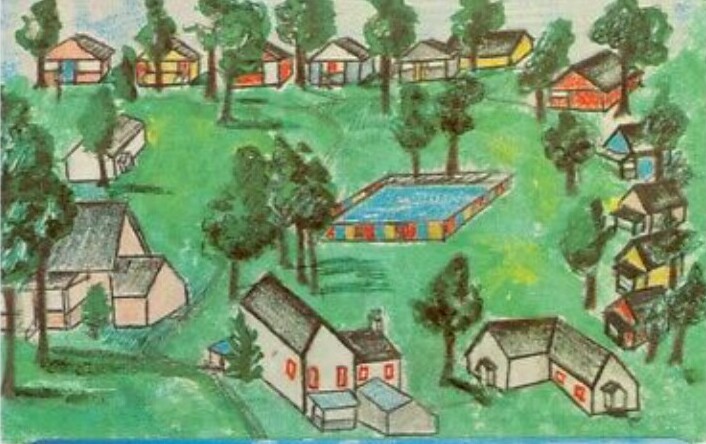

There was plenty of other propaganda around to influence us; I remember drawing a picture of a falling atomic bomb I labeled “Happy Birthday Joe”, and it was not Stalin’s birthday. Later, as a grownup, I would dream a few times a year of silo doors blasting open and missiles sailing out, whether their missiles or ours I never knew. These were not quite nightmares, I was a passive onlooker, but were not pleasant to wake up to at three in the morning. After the Soviet Union collapsed and the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the world felt safer and the dreams pretty much stopped.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, one of my customers asked if I had sent my family to stay with relatives at the shore, farther away from New York City, a likely target. He was wide-eyed and genuinely frightened, and couldn’t understand why I wasn’t frightened too. That was a good question – I think I just couldn’t believe that either the Russians or us would do anything so crazy.

From a 1963 Department of Defense internal newsletter:

THE SHELTER SIGN. How many really understand the real significance of those black and yellow markers? There are six points to the shelter sign. They signify: 1. Shielding from radiation; 2. Food and water; 3. Trained leadership; 4. Medical supplies and aid; 5. Communications with the outside world; 6. Radiological monitoring to determine safe areas and time for return home. … It is an image we should leave with the public at every opportunity, for in it there is hope rather than despair.