I still have my night job at the A&P warehouse so there’s no rush. My resumé is pretty good for someone who hasn’t actually worked in computing yet – the 725-hour programming course at Automation Institute gets respect, but it’s not enough to hire me on. Everyone wants experience. I don’t have much luck getting interviews in New Jersey, so I decide to bite the bullet and look for a job in New York City. After a few interviews in run-down employment offices with computer illiterates who act like they’d be doing me a favor to send me to a potential employer, I strike pay dirt.

It’s April Fools’ Day, 1968 and I am at the classy Robert Half employment agency in midtown Manhattan. In honor of the day, station WQXR plays Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks in the background. I have a good interview, and next day get a call that Condé Nast Publishers would like to interview me next week. They, too, are a classy outfit, so classy (I later learn) that they have a special print chain on their printer just to produce that fancy é with an accent in their name.

My interview with HR (“Personnel” then) goes well; I am all tweeded up in my pgood suit and overcoat, looking British and carrying a rolled black brolly. Optics out of the way, I next interview with Mr. Harrison, the manager of “the IBM Department”. He sees that I have mad 1401 computer skills, and we hit it off otherwise. He introduces me to Tom, the other programmer, and we three go to lunch.

I am hired. Condé Nast publishes Vogue and Glamour magazines, so there are models and other alluring creatures running loose through the building, but our floor, the 4th, is 100% business. The fashion magic all happens upstairs.

Starting home on the subway from my first day at work, after I get off the crosstown shuttle I am confused, and I get directions to the 7th Avenue line from an NYPD police officer. The next day, at the same spot, I am confused again and ask an officer for directions. He answers “Same way I told you yesterday”, and walks away annoyed.

After a week riding the subway, I retire my bulky attaché case, which tends to get tangled up in other people’s legs, in favor of a $4 generic zippered black leather portfolio I see in a drugstore window. I normally carry it at my side, but in a really tight subway car I clutch it against my chest like a frightened girl.

If I get close enough to my office window to get the right angle, I can see the foot of the Chrysler Building, with its crowd of Vietnam War protesters.

I design and write programs in Autocoder assembler language, lots of them. I must be good at it, because I get a raise. I am particularly proud of this latest program because it works almost immediately, and the output is perfect. It’s an analysis of reader responses to a survey in one of the magazines. I show the printout to Mr. Harrison, who studies it and says something like “Hey, that’s really good”. Then he adds “Uh, you spelled questionnaire wrong” and chuckles. I laugh too, but it stings a little.

Tom and I and our boss generally stick together. We seldom leave the 4th floor except to get lunch downstairs in the Back Bay restaurant, which is not as expensive as it sounds. Every other Friday is payday, when we go up to the 11th floor to pick up our checks.

One payday we start for the 11th floor, just us three in the elevator, when it stops at the 6th. In steps one of the models, not at all self-conscious despite wearing the latest in fashion, a see-through blouse, no bra. The fabric is sheer and her breasts are lovely. Following some instinctive sense of decency, the three of us avert our eyes, and now with heads tilted back we stare at the ceiling in silence until she reaches her destination. She exits and the doors close. As the car begins to move again, we gleefully exclaim in unison “DID YOU SEE THAT?”

Sometimes at lunchtime we walk around midtown, trying not to look like tourists. It’s best not to look up, or stare at anyone. There’s a blind man who usually stands near our building selling pencils; people drop money into his cup but don’t take a pencil.

One day Mr. Harrison, Tom and I have lunch with Diane, our IBM Sales Engineer, who is dressed for the times in miniskirt and white knee boots. The subject turns to commuting and I say I’d love to live in the city, but there’s no way all my family’s stuff would fit in an apartment. Diane says I’d be surprised how much stuff can fit in an apartment, and would I like to see hers? I say something like “Thanks, but I don’t think so” in the politest possible business-neutral way. After lunch, Tom turns to me and says “You’re crazy, man!” Yes, I probably am.

The classic IBM blue THINK sign is available in other languages and colors for those who like to show off. Mr. Harrison’s boss, the head of accounting, has one on his desk.

Even the company’s benefits are classy. For the one-year anniversary of their start date, women receive flowers, men receive a boutonniere. These are delivered to us at our desks by flower-shop courier. Each December, everyone gets a half-day off to go Christmas shopping.

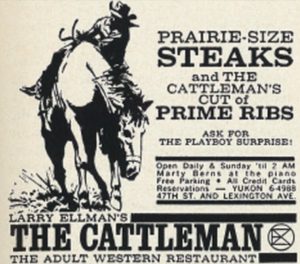

This December brings a disappointment: the company Christmas party is cancelled due to the Hong Kong Flu. Mr. Harrison still wants to have a department Christmas party, and one day around noon we head for the Cattleman steakhouse. We are Mr. Harrison, Tom and I; computer operators the ladylike Ginny, methodical Steve, and barber-school-regular George; six or eight keypunch girls (‘operators’, sorry) and their leader Marie. We fill a long table in a private room. We will pay for our own drinks and split the rest of the bill. Most of us opt for the prime rib, which is excellent.

The keypunch girls are fun – we don’t usually see them because they work in their own, noisy room. I know two of them, Susan the long-haired girl from across the river who seems to have a thing going on with the IBM repairman who refuses to wear a white shirt; and Marika, fresh off the boat from somewhere in Europe, not much English yet, but not much is needed to punch names and addresses into cards.

On the way back to the office we break into loose groups and I get separated. I’m a little drunk. The city is beautiful at Christmastime. As I walk by the Pan Am building, I hear music and step into the lobby. A choir is singing Christmas carols.

Everybody at Condé is nice, the work is rewarding and I love my job, but the commute is getting me down.

From my house to work it’s only eight miles as the crow flies, but it’s a 4-seat commute with a lot of walking; even on the best days it takes 50 minutes. Coming in, I take the Newark subway to Newark Penn Station, then the PRR train under the river to New York Penn Station, then the 7th Avenue subway to 42nd Street, then the shuttle over to Grand Central. I get tired again just typing that in. At each connection there’s a walk and sometimes a bit of jostling to get from one conveyance to the next. I start thinking about another hot summer underground.

Beyond the commute, two events help me make up my mind.

-

-

- As I stop-start walk up the crowded stairs from one subway line to another, an aggressive old lady behind me keeps stepping on the back of my shoe; she seems to be trying to actually stand in my footprint. I am carrying a rolled umbrella with a metal tip, and I let it hang down far enough at my side that she runs her instep up under it and backs off.

-

-

-

- A newsstand vendor trying to sell out an earlier edition of the Post puts the late edition with closing stock prices underneath the earlier one. When I ask for a copy of the edition underneath, a reasonable request, he refuses. Not in anger but in a matter-of-fact way, I say “Well, fuck you then.” He replies in the same unemotional tone, “Fuck you too.”

-

So, I have soft-stabbed an old lady and said “fuck you” to a total stranger. It’s time to get myself out of New York, and also an opportune time to get my family out of Newark. I call an employment agency and ask them to find me a job as far south in Jersey as they can.

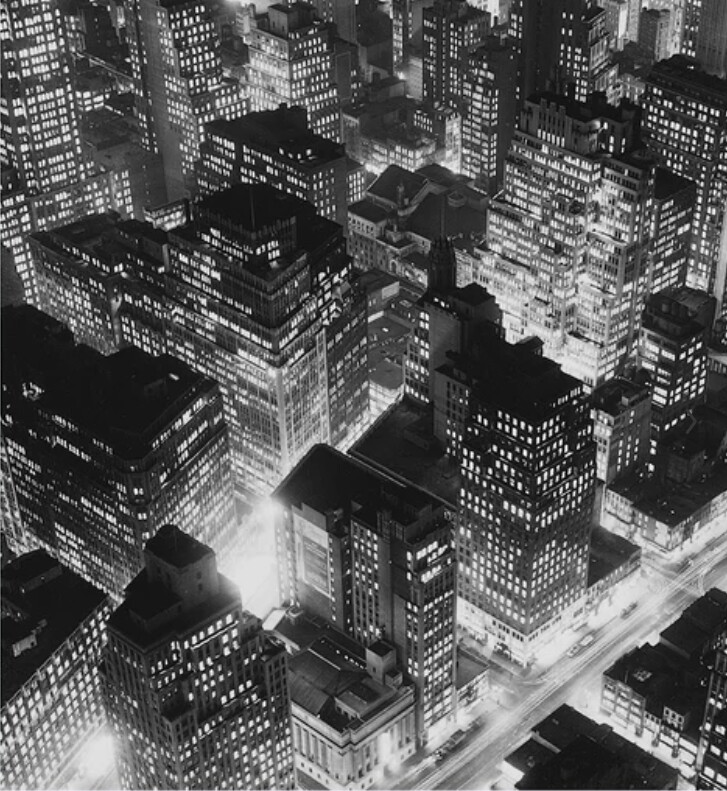

About four years later, I am in the city and stop by for a visit. One of my programs is still running every day. Whenever I see a photo of Manhattan with its million lights and offices, I say to myself, “I made a difference.”