Plinth, the original title of this article, is an odd-looking word. It means “a heavy base supporting a statue or vase.” My wife Mimi and I first became aware of the word when we were in England on vacation in 1989.

I know the year was 1989 because I looked up the date the newly-repaired Portland Vase (pronounced “Vahhhse” if you are British) was restored to its plinth at the British Museum.

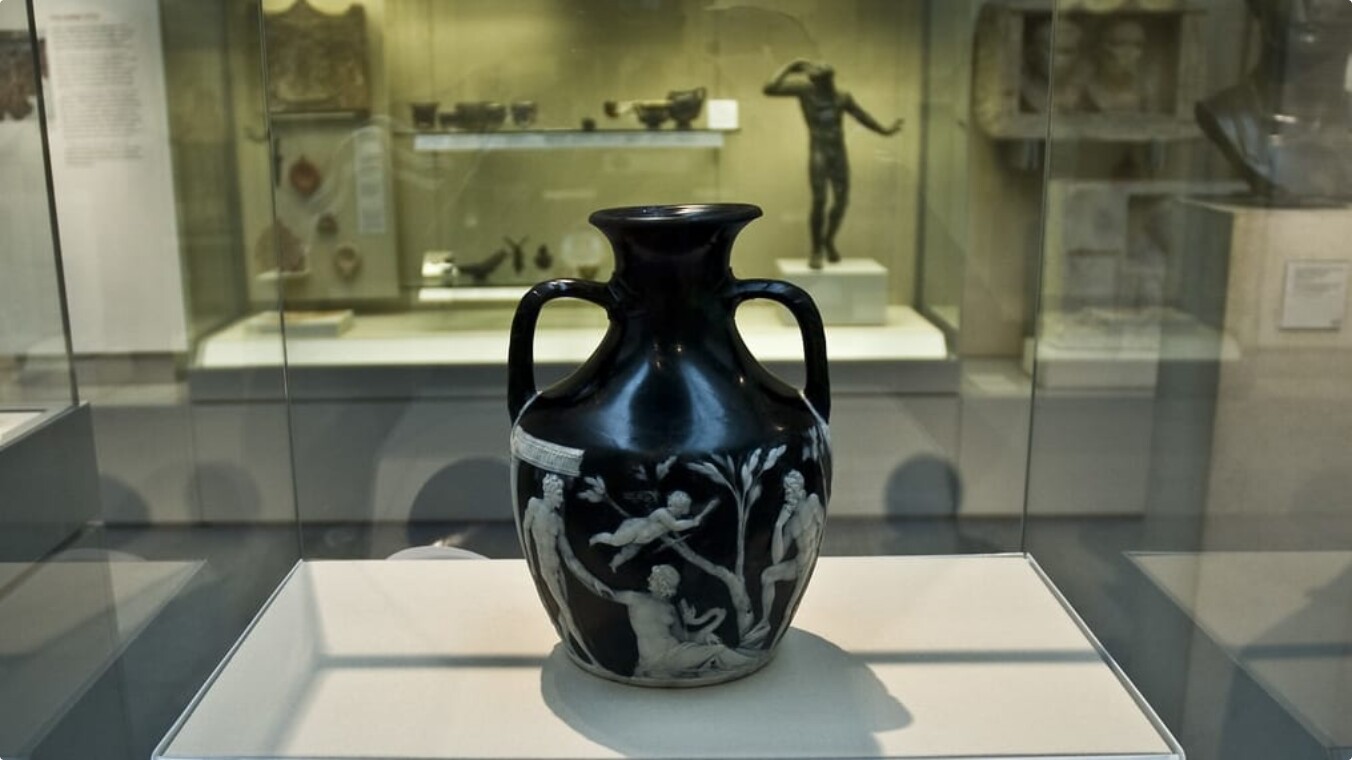

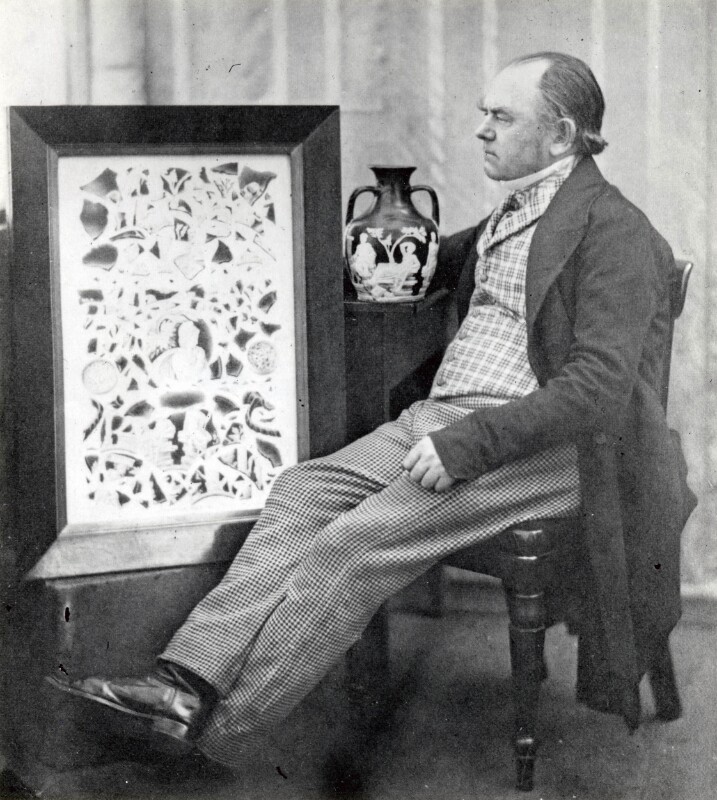

That much-celebrated artifact, a violet-blue Roman glass urn taken from the tomb of Emperor Alexander Severus, is probably the most famous glass object in the world. Believed to date between A.D. 1 and A.D. 25, the first recorded mention of it was in 1601, as it began its travels among the collections of Pope Urban VIII, Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, and several noble Roman families including the Barberinis. During those years the vase was known as the Barberini Vase.

In the 1770s, it was sent to Britain in repayment of gambling debts incurred by Donna Cordelia Barberini. From there it came into the possession of the 3rd Duke of Portland, earning it the name it is known by today. After further travels, in 1810 the vase was transferred safely to the collection of the British Museum—so far so good.

But one afternoon in 1845, a drunken student named William Mulcahy threw a heavy sculpture onto the artifact’s glass case, smashing the vase to pieces (189 of them, to be precise), and precipitating years of news stories and three vase restorations. The first two restorations were unsatisfactory—as time passed, the glue yellowed and became visible. The third and most recent restoration, completed over the 1988 Christmas holiday, took nine months and used modern adhesives and methods. That restoration was pronounced a success and predicted to last 100 years.

This is where Mimi and I come in. We had been wandering through the museum admiring such treasures as the Rosetta Stone, taken from the French after their 1801 defeat in Egypt, and the so-called Elgin Marbles, decorative friezes stripped from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s. We came to a room devoted to artifacts of the Roman Empire.

The Portland Vase wasn’t in the room yet, but shortly after we entered it was rolled in and placed on a plinth by a solemn procession of guards, curators and officials.

Having never heard of the Portland Vase, and knowing nothing of its history, I was curious about the object that had been brought into the room with such ceremony.

Being an American, I walked over to get a better look, ending up about three feet away. The vase was not yet enclosed in protective glass, and was truly beautiful. Its guards were not prepared for the sudden appearance of this much-too-close visitor, and froze. Could it happen again? Time stood still.

Surprisingly, no one tackled me or tried in any way to move me away from the venerated object.

After a minute or two, I finished my inspection, rejoined Mimi and we moved on.

Special thanks to restoration site sylcreate.com for their article “A restoration 144 years in the making – how the Portland Vase was restored to its Roman glory”