I can’t remember where I was working at the time, but I remember a discussion with a co-worker whose wife had just had their first baby, and him saying, “I want my son to have a job with a chair.”

Here’s part of my own strange path to a job with a chair.

Studying the market, 1960s

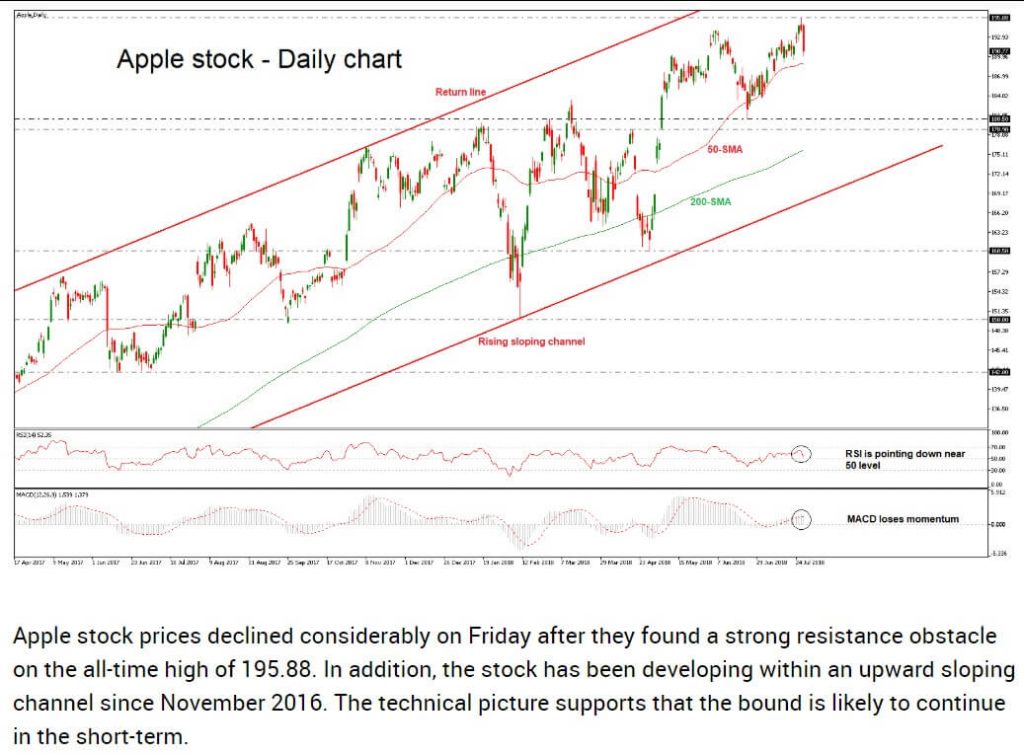

When I was driving for Dugan’s Bakery, I got interested in the stock market. I studied the Wall Street Journal and Barron’s Magazine, and bought a couple of stocks, Clorox and Reynolds Tobacco. They went down instead of up, so I tried to figure out where I went wrong, and became interested in technical analysis, a way to predict where a stock price is headed based on how it’s behaved in the past. Mostly it works, but sometimes it doesn’t – it’s more of an art than a science. I kept daily charts on about 20 stocks.

If I finished my route early, I sometimes stopped in at the Nugent & Igoe brokerage in East Orange, where my broker was Walter ‘Tiny Hands’ Wojcik. If you ever went by and saw a bakery truck parked around the corner, that was probably me. There were eight or ten regulars who hung around watching the electronic ticker tape crawl along one wall, and, when inspiration struck, speed-walking over to their broker’s desk to make a trade. The room was not unlike an OTB horse parlor, and the tone of the conversation was similar. Maybe that’s another article one day.

Collecting unemployment

After Dugan’s was sold down the river in 1966, I collected unemployment for a few months while applying for stockbroker jobs in New York City. Meanwhile, I subscribed to a weekly chart service and continued to make small trades and read all the financial stuff I could get my hands on.

I learned one thing about unemployment that I’ll pass along: if you show up for your weekly appointment wearing a suit and tie, they’re not going to hassle you too much. So, Mr. Smithee, you want to be a stockbroker but have only the most remote of qualifications? Here’s your check, and good luck with next week’s search. After many weeks they got sick of seeing me, and put me with a group of others who hadn’t found jobs, to take a manual-dexterity test with a view toward getting us assembly line jobs somewhere. That’s another article some day, too.

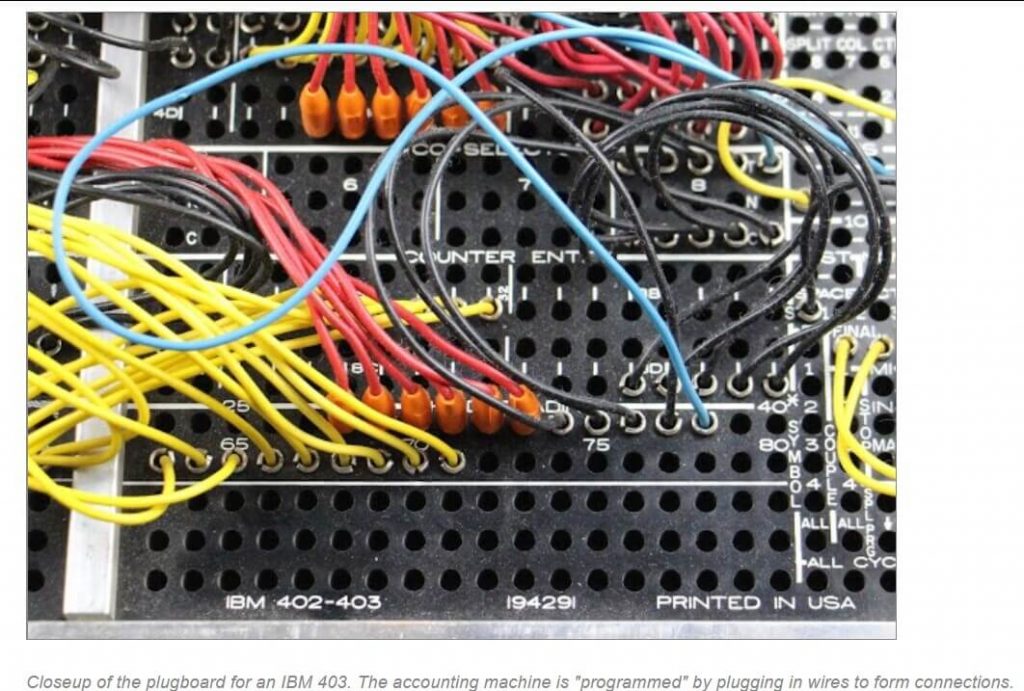

At the Nugent & Igoe office, I was friends with a young guy named Jerry, who would look over my shoulder at my charts. He said if you like doing stuff like that, you should get into computers. There was a programming and control-board-wiring school directly across the street, and I paid them a visit. Programming school was not in session, but they showed me their accounting machines and the control boards, and I fell in love with the boards’ combination of complexity and orderliness. I filed Jerry’s career suggestion in the back of my mind.

Mayflower Securities

A while after Dugan’s went out of business, I got a call from Tommy MacMillan, a former supervisor who knew I was interested in the stock market. He suggested I might like working for Mayflower Securities. At the time, Mayflower was on the level; I know that because I asked my bank to get me a Standard & Poor’s company report on them.

My eventual manager Skip Zarra had no interest in the finer points of the stock market or investing; his only interest was in making sales. During my interview, he asked who in the world of finance I most admired, but didn’t recognize the name Jesse Livermore, a famous day trader, and on and off one of the richest people in the world. That’s not exactly a black mark on Skip, but it tells you something.

Mayflower and other securities firms sent their prospective brokers, aka “registered representatives”, to an intensive three-weekend securities course held in a classroom in the instructor’s home in Union. As I recall, we had to pay for the course ourselves; fair enough, I suppose. The object was to pass the SEC Series 7 Examination to get our brokers licenses. I’ll let the SEC explain it:

“Individuals who want to enter the securities industry to sell any type of securities must take the Series 7 examination—formally known as the General Securities Representative Examination. Individuals who pass the Series 7 examination are eligible to register to trade all securities products, including corporate securities, municipal fund securities, options, direct participation programs, investment company products, and variable contracts.”

Next we took the examination, which was multiple-choice. I’ve always been a good test-taker, and I passed.

A company dinner

Mayflower gave a Christmas dinner for their sales people and spouses. I’m not sure if there were any female sales people at the time, but there might have been. It was at a fancy restaurant, and the sky was the limit. Mimi and I were seated with Skip and Tommy and their wives, and there was good conversation all around. No introductions were offered beyond an informal “Hi, I’m…”.

After the meal Gene Mulvihill, founder and owner of the company, got up to give a motivational speech. During the speech, Skip leaned over and whispered to me “His wife owns thirty percent of the company”. I whispered back “Yes, I know” and he seemed surprised. During a lull in the conversation later, he asked how I knew about Gene’s wife’s partial ownership, and I said it was in the company’s S&P report. He next asked how I had come to see an S&P report on the company, and I said I had asked my bank to pull one for me. This did not go over well, and he said “You pulled an S&P report on us? YOU pulled an S&P on US?”, as though the world had turned upside down.

A couple of weeks later, I phoned Tommy’s house with a procedural question and his wife answered, She said he wasn’t home, and asked if she could take a message. I said “Yes, this is Paul Smithee”, and when she didn’t respond, added “We met at the Christmas party.” After a second, she said “Oh, at the Christmas party, right.” The next day, Tommy phoned to ask what my question was, and also said “That wasn’t my wife at the party.” I apologized profusely, but he said it was his own fault for not properly introducing his friend. When I passed this news along to Mimi, she was not surprised, and said “I thought there was something funny going on with them.” Hey, thanks for telling me.

Early on, I went to Brooks Brothers and invested in an expensive three-piece British tweed suit and a good tweed overcoat. I wore them to every job interview and important meeting I had for years afterward. I also bought a new car, a ‘67 Valiant, partly to impress clients that I had a new car, and partly because I needed one. That car lasted a long time, almost as long as the suit, which eventually no longer fit.

Making sales

After we were SEC-licensed registered representatives, we were trained to go to commercial areas such as strip malls and ask small-business owners “Has anyone ever talked to you about mutual funds?” Mutual funds were just then coming into their own and getting a lot of positive press coverage. We sold monthly investment plans in Oppenheimer and Dreyfus funds, nothing shady about either one, both are still around today. The SEC required we make potential clients aware that half their first year’s investment went toward sales commissions, so it would be important that they continue the plan and not cash out early. Some salesmen conveniently forgot to mention that point, but I never did.

I sold an Oppenheimer monthly plan to my upstairs neighbors; they needed to cash it in the next year and took a big hit, and I felt bad. I also sold an Oppenheimer monthly plan to a restaurant owner who I happened to catch during the afternoon lull. When I went to his home to pick up his shares of AT&T to sell to pay for the Oppenheimer, his family was very suspicious of me and the whole deal, but over the years he got a much better return with Oppenheimer.

As a kid trying to sell newspaper subscriptions, I realized right away I was no salesman. Looking back, I was too ready to accept the prospect’s first “no” and move on, instead of trying to counterpunch and wear down their resistance. Mayflower encouraged us to talk to 30 people every day, and I bought a pocket clicker to keep track. Hairdressers always seemed to have time to talk, but they never bought anything. One day working my way through a strip mall, I spotted a city worker hand-digging a hole for a traffic sign. I walked over and said “Excuse me, but has anyone ever talked to you about mutual funds?” He looked up and said “No entiendo.” Even as I clicked my clicker to count the contact, I knew I was just kidding myself.

Shady doings

I finally quit Mayflower when they changed their philosophy and wanted us to start pushing penny stocks they bought by the bushel, instead of standard, legitimate mutual funds.

Mayflower was later absorbed by the infamous “pump and dump” penny-stock outfit First Jersey Securities. First Jersey was headed by Robert Brennan, later described by Forbes as “a swindler of a recognizable type: totally unscrupulous, with the nerve and audacity of a second-story man”. In 2001, Brennan was found guilty of money laundering and bankruptcy fraud, and sentenced to nine years in prison.

After looking into other schools, I used the GI Bill to register for a computer programming course at Automation Institute, and an old friend gave me a lead on a night warehouse job I could work at while I attended school during the day. I was on my way.