Movers and shakers

With few exceptions, the people I worked with at Insco were good, friendly people, and I miss them. Seeing the building being torn down last year made me very sad.

Arthur

When I started at Insco, I inherited maintaining one of Arthur’s older insurance programs, and got to know him. He was an incredibly productive programmer and a CPA – a mad genius who could write an entire property insurance system without a written specification, based only on Insco’s contract with some far-off state agency, inventing the parts that were necessary but not written down. It seemed like he worked 12 hours a day; any night I stayed late I’d pass his desk on my way out, him still furiously spinning out code, surrounded by cigar smoke and stacks of program listings. Arthur was old and gray and frail, and he loved the company and his work.

I had known Arthur for only a year when I saw his name on the local newspaper’s obituary page. He died in Jersey Shore hospital, no mention of the cause. He left behind a wife and five children, a terrible thing, but to me most terrible was that this worn-out old man was only 48 years old. I kept a copy of his obituary to remind me of what’s important.

Paul Prinzhorn

Paul was a young programmer and philosophy major who was taking a night course in statistics at Rutgers-Newark. As he started home one night, he was stopped by two locals who wanted his wallet and briefcase. He resisted, and they stabbed him to death. When I heard, I thought, one more crime that will never be solved. But while writing this I found out, via newspapers.com, that the two were identified by a witness, arrested, and in 1982 sentenced to life in prison. 1982 is a long time ago, but I hope “Life” means life, and they are still there. That’s why I pay taxes.

Paul was a young programmer and philosophy major who was taking a night course in statistics at Rutgers-Newark. As he started home one night, he was stopped by two locals who wanted his wallet and briefcase. He resisted, and they stabbed him to death. When I heard, I thought, one more crime that will never be solved. But while writing this I found out, via newspapers.com, that the two were identified by a witness, arrested, and in 1982 sentenced to life in prison. 1982 is a long time ago, but I hope “Life” means life, and they are still there. That’s why I pay taxes.

Don’t resist, friends. I know it goes against every normal instinct, but don’t.

More Gordon

Gordon and I got to talking about when I worked at Hess. He dismissed the Hess notion of keeping people in the building at lunch time with a cafeteria that served great and unlimited food for only 50 cents a day. I told him Hess had another great idea; cafeteria staff rolled a cart into your department twice a day with free coffee, juice and soda. He looked at me as though I was crazy, but I said Hess saw it as win-win because the employees weren’t burning up time going back and forth to the cafeteria. He seemed to like the idea better after that, but didn’t say anything more and I forgot about it. A few weeks later I heard a buzz of excitement down the hall, and here came a cafeteria lady, pushing a cart of coffee, juice and soda, AND a selection of pastries. The catch? She also had a little cash box to make change: none of it was free; Gordon wasn’t giving anything away. Everyone was happy about the great new convenience, but only I knew what might have been.

Tech manager Bob

Bob was the first manager of the technical unit, the collection of programmers that fed and tended the two mainframe computers. I knew IBM 360 assembler language, which is how applications “talk to the metal” as they say, and when an opening in the unit came up, I interviewed with Bob and was offered a transfer. Special thanks to Phil Keating, the vice president who did not oppose my transfer out of his area.

Kermit Says

Bob had a strange approach to managing, but it worked. I don’t know if he did it to keep us entertained, or because he had a mental block about directly assigning work. He’d put a sock puppet on each hand (one was Kermit, I forget the other), crouch behind his cubicle wall, raise his hands and start a Muppet-voiced conversation:

Kermit: IBM sent us an operating system update!

Not Kermit: I hope it fixes all the bugs!

Kermit: Me too, but we’ll have to shut down the system to install it!

Not Kermit: Oh no!

Kermit: It’ll be alright, we’ll all come in at six o’clock tomorrow morning after production finishes!

Not Kermit: That sounds great! See you there!

Tech manager Dennis

When Bob left the company for more money, we got a new manager, Dennis. Dennis had a peculiar loyalty to the hardware brand Itel (sometimes misread as Intel), a cheaper non-IBM brand of disk data storage, and he persuaded Insco to install eight units. Itel was a subsidiary of Hitachi, a Japanese company, and thus automatically on the wrong side of Gordon, a veteran of World War II. Gordon took quiet satisfaction in every Itel hardware failure, which were common. When an Itel unit failed, their service person sometimes had to drive to the Army base at Fort Monmouth, about ten miles away, trading circuit boards back and forth between the two sites to isolate the failure to a single bad board. Dennis once asked me to make up a six-letter name for a new Itel unit, then was unhappy when I chose BRANDX.

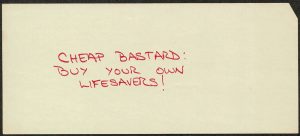

Dennis was a bit shady, and he’d roam the department in the evening, searching for candy or gum. I kept this note in my pencil tray. It seemed to work. Notice how it suggests that nobody actually knows who “cheap bastard” is.

Dennis was a bit shady, and he’d roam the department in the evening, searching for candy or gum. I kept this note in my pencil tray. It seemed to work. Notice how it suggests that nobody actually knows who “cheap bastard” is.

As the company added programmers, the VM system slowed down, and a faster machine was needed. I don’t know every detail of what happened next, but here’s the general idea as best I understood it. Remember I’m not a hardware expert.

When Gordon read the specification for the newly announced IBM 370/148, it appeared to be 20% faster than our current computer, a 360/67. Dennis said Gordon didn’t understand the specification – although the cycle speed was faster, the 370/148 would require more cycles per instruction, meaning any given unit of work would take about four times as long as on the old machine. Gordon disagreed with Dennis’s interpretation. There were heated arguments, but Gordon outranked Dennis, Dennis gave up, and a 370/148 was ordered.

Gordon was a great manager and negotiator, but not an expert in the fine points of computer hardware, and his interpretation of the 370/148 spec was wrong. The 370/148 was installed, and as more users arrived at work on its first day, performance went from slow to terrible. After a few hours, the users were ready to riot and Gordon took me aside to ask, in an indirect way, about the possibility of sabotage. No, there had been no unauthorized changes, by Dennis or anyone else. It took two or three days to get the old machine reinstalled, then IBM helped Gordon choose a better, faster model. The whole thing was a disaster, and a huge embarrassment for Gordon. For me, the worst part was that Dennis was right.

Jenny and me? Nah.

One more thing about Gordon. I never saw it in his dealings with me, but apparently he could be impatient and nasty in his dealings with his secretary, Jenny. She and I were friendly and she knew I understood Gordon, and one day she came downstairs in an emotional state, looking for some sympathy. She appeared in my office doorway and asked if she could come in. Of course she could, and I closed the door. (How different things were then!) Gordon had finally worn her down, and she spent the next five or ten minutes crying about the way he treated her. I can be sympathetic when I want to be, and she eventually calmed down. I opened the door and she left, still red-faced. Meanwhile, my own secretary, not the sharpest knife in the drawer, had been listening at her desk outside the door. Based on all the crying, she tried to float a rumor that Jenny and I were lovers, but nobody was buying it.

Crashing

Before there was VM, there was CP-67, a predecessor that ran on an earlier IBM machine, the 360-67. I call them both “VM” here for convenience, and because for people developing programs there wasn’t much difference, except for the terminals/workstations. Invented before the silent CRT, the noisy 2741 terminal was based on the IBM Selectric typewriter and printed the same way, by banging a typeball through an inked ribbon onto paper, one letter at a time in a machine-gun clackety-clack.

In the early days of VM, you could expect at least one system crash a day, sometimes more. People made a habit of issuing a “Save” command every few minutes, sometimes more often, to minimize how much work they’d have to repeat after a crash.

On a VM system with the noisy 2741 terminals, a computer crash really was a crash. Suddenly the room went silent and all keyboards locked. For a second, the human mind imagined the silence might be a coincidence, that maybe everyone was forming a new thought and had stopped typing. As the silence stretched into several more seconds, we accepted that the system was crashing under us; the silence was the system organizing itself to restart. During those last seconds, there was a collective sigh – we knew any work since our last Save was lost.

The silence ended with an actual crashing sound – every terminal in the room simultaneously banged out the system’s Welcome message, “IBM CP-67/CMS online”. The best way to think of that sound is to imagine a stack of dishes dropped straight down, staying together until they hit the floor. That sound confirmed the system had indeed crashed, and was followed by a dispirited “Awwwwwwww.”

Charles

Charles was a programmer who smoked a lot of marijuana. Maybe he was stupid already, but who can say.

One day he was sitting next to me in the terminal room. In his befuddled state, he typed in a command that deleted the only copy of the program he had been working on. He still had a paper listing though, so he began typing it in. The program was relatively small, maybe 200 lines of code. After he’d been typing for an hour or so, the system crashed, and Charles let out a sad “Ohhhhh.” I could tell he hadn’t saved his work, because he went right back to the top of his listing and began typing it in again. After a while the system crashed again, and he put his head down as though he was going to cry. I said “You didn’t say ‘Save’ this time either?” He hadn’t.

He looked so upset that I felt sorry for him. I wasn’t his boss, so I couldn’t tell him what to do, but I made a sort of tough-love suggestion. I said “Why don’t you take the rest of the day off, go home, and think about whether computer programming is the right line of work for you?”

He did leave for the day, and the story had a happy ending, for both Charles and for Insco. A few weeks later, Charles gave notice. He’d found a better job, as a programming consultant for one of the big accounting firms. Those of us who heard just rolled our eyes.

James and the Giant Printer

Insco ordered a high-speed laser printer, the new IBM 3800. The VM operating system didn’t support the 3800, so IBM arranged time for us to develop our own support code in their Madison Avenue office. We would give IBM a copy of our changes to provide to other 3800 buyers. VM shops were a small, friendly community in those early days, and innovations were freely shared.

Jim was a systems programmer who knew his way around VM, and was also an expert mechanic who kept his church’s old school bus running and getting parishioners to church each Sunday.

After some planning, Jim and I headed for New York. We brought along a copy of Insco’s own customized VM system, on a disk pack in one of those plastic carriers that looks like an oversize birthday cake. Boarding the subway for the trip uptown to IBM, I suddenly imagined that our system might be erased if we sat too close to the motors, and we kept to the center of the car. The system survived just fine.

Insco was reasonable about letting people stay in a hotel short-term rather than commuting back and forth, and that’s what we did. After we finished up each evening, we had a leisurely dinner and headed back to the hotel. James was not a drinker and kept to his room; I headed for the hotel bar. In moderation, of course.

I think we were in the city four days, changing code and running back and forth between our workroom and the seemingly locomotive-sized printer. We used up a lot of paper getting that monster working, but it finally did, quietly and at great speed.

Insco’s own 3800 arrived one weekend and was installed dead center in the computer room. It took up a lot of space and was the first thing you saw when you walked in. When I got my first look, I was surprised and disappointed: our world-class, superfast printer was crooked. Instead of sitting parallel to every other piece of equipment in the room, it was misaligned, just enough to look a bit silly. The computer-room manager said the installers had a terrible time with it (it weighed 2200 pounds), and said the resulting position was the best they could do. The manager’s vice president said it wasn’t off by very much, and did it really matter? I was not happy, and for a while I had to see it every day.

Chairman Ricker

I never met Continental’s chairman, but he became something of a hero to me. On his next visit to Neptune, the first thing he said when he saw his new printer was “Why is it crooked?” Nobody tried to convince him it wasn’t, and it got fixed.

When you’re the chairman, it’s easy to make things happen. He often flew between the New York and Chicago offices, 720 miles, and when he became chairman, he adjusted company policy to allow first class travel for any trip exceeding 700 miles.