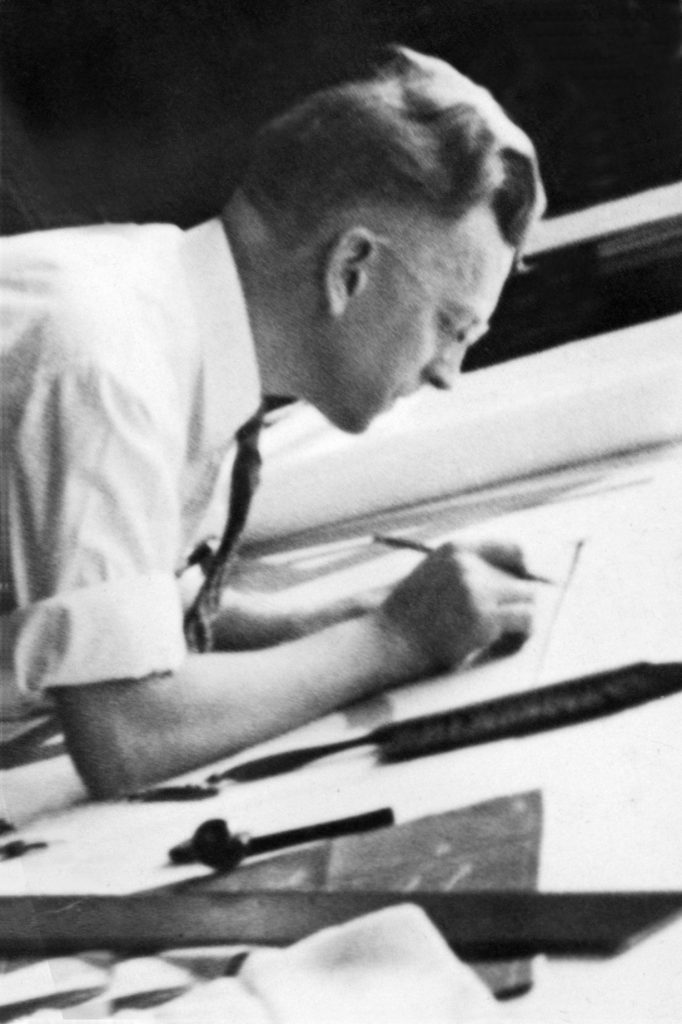

My Uncle Bert (Herbert, actually) lived in Temperance, Michigan, farm country just across the state line from Toledo, Ohio. He worked as a pattern maker and draftsman in the auto industry and was a car lover who had owned a Stanley Steamer in his youth. He was a good man who was like a father to me. I miss him and think it’s sad that he had to leave New Jersey to seek his fortune.

A gentleman farmer, he had a house on eight-and-a-half acres of land and raised chickens as a hobby. The warm eggs were collected each morning by his daughters. They sold some, and Bert brought some to work.

Starting at age 10 in 1948, I was invited to stay with Bert and his family over two happy summers. My mother tried to give him money for the expense of feeding me, but he refused it.

His only son Herbie was born with Down syndrome, a disability I didn’t recognize until I was older. I thought he was just a person without a lot to say, not too bright and with thick glasses. When he did speak, he was hard to understand. He had three older sisters. They knew how to sew, and made their own clothes. As far as I know, their dressmaking wasn’t a money-saving thing, it was a country, small-town craft thing, and perfectly ordinary – they probably took sewing classes in high school . I think a high point for them was choosing from the local feed store’s 100-pound patterned-cloth chickenfeed bags whichever patterns would make the prettiest blouses. I remember Uncle Bert lifting and pulling the heavy bags, shifting them around to get to the ones his girls liked.

Unlike Bert, his wife Evelyn was Catholic, a woman of Irish background who raised their kids Catholic as well. Virginia, the oldest, was in training to become a nun until her order sent her home before final vows when she contracted tuberculosis. That pretty much did it for Bert with the church. Virginia got well, and she and her sister Charlotte became nurses, often working in the same hospital and vacationing together. Naomi, the youngest girl, became a teacher.

Herbie had a friend from one farm away named Alec, who was about 14, the same age as Herbie. I was probably four years younger. Thinking back, Alec may have been just a bit limited also, but he drew fantastically detailed and lifelike pencil studies of animals and birds. One evening Herbie and Alec invited me to come along while they looked in windows, I guess a regular practice. I went along but not enthusiastically. I was worried we’d be caught, and we didn’t get to see anything anyway.

We spent a lot of time together walking around the “neighborhood”, really just other farms. One day I noticed something different about some barbed wire we had just come up to, the barbs were longer and sharper than what I’d seen before. I mentioned this just as I touched the point of one, getting a healthy shock. My tour guides thought this was hilarious. Fun fact: electrified fences can be recognized by the white porcelain insulators holding the wire onto the fence posts.

One excursion that I won’t forget was a visit to a nearby farm that raised pigs, on Castration Day. I think I may have been brought there by my pals for shock value as much as for my education. The castration procedure is quick, but to this city boy even years later seems astoundingly cruel. A young pig is caught, held down, his back legs spread and his ‘gear’ vigorously cleaned with a stiff paint brush and pink antiseptic from a bucket. The testicles are squeezed together, sliced off with a straight razor and dropped into another bucket. The wound is then repainted with the pink antiseptic and the pig released. No anesthetic is involved, and the pig squeals/screams from the moment it’s caught. I asked one of the young guys involved the reason for the procedure; the answer was it makes the pig get fatter and be better behaved.

At night on Dean Road it was pitch black and dead quiet except for the crickets and frogs. I slept on the living room couch. The rare times a car went by it could be heard coming from far down the road, then its lights seen through the screen door as it passed. The traffic was so light and random it was hard to get used to. My hosts didn’t seem to have many books, at least not in the living room; the only one I remember was a hardbound illustrated medical book of chicken diseases.

Bert’s (healthy) chicken yard was maybe 30 feet by 30, with the coop where the chickens roosted at night at one side, and in the center a long-unused outhouse. When Bert and Evelyn had friends over who had never visited before, when they asked for the bathroom Bert would walk them out to the chicken-yard gate with a flashlight to see how far they would go. Just out of curiosity I used the outhouse once, it was smelly.

I had brought my cap pistol and holster along. Chickens wandered loose in the yard alongside the house, pecking the ground for insects and whatever looked interesting. I would walk up behind one, take aim and pop off a cap or two. After a while one rooster took exception to being a regular target, jumped up and spurred me in the leg. My pants were heavy enough that I didn’t need stitches, but I did bleed quite a bit. A couple of weeks later Evelyn was planning a chicken dinner and Bert asked if I had any thoughts on the subject. I pointed out my attacker and Bert caught him, then trussed him up so he couldn’t move. Bert was a civilized man, and didn’t like chickens running around the yard spraying blood after their heads were chopped off. I asked if I could do the honors and Bert nodded. He stroked the bird gently for a while, then stretched him out on the tree-stump execution block. I managed only one timid tap of the hatchet before Bert said “Give me that.”

There’s a lot more to a chicken dinner than killing a chicken, and I felt somehow deflated and a little sad watching his innards be removed, then his carcass soaked in scalding water so the girls could more easily pull out his feathers, a tedious task. When we had our Sunday dinner, I ate some, but not as much as I normally would.