“On the morning of 15 October 1927, a dim, autumn day, a group of men foregathered at the Rosedale cemetery in New Jersey and picked their way through the headstones to the grave of one Amelia — ‘Mollie’ — Maggia. An employee of the United States Radium Corporation (USRC), she had died five years earlier, aged 24. To the dismay of her friends and family the cause of death had been recorded as syphilis, but, as her coffin was exhumed and its lid levered open, Mollie’s corpse was seen to be aglow with a ‘soft luminescence’. Everyone present knew what that meant.” –The Radium Girls, Kate Moore

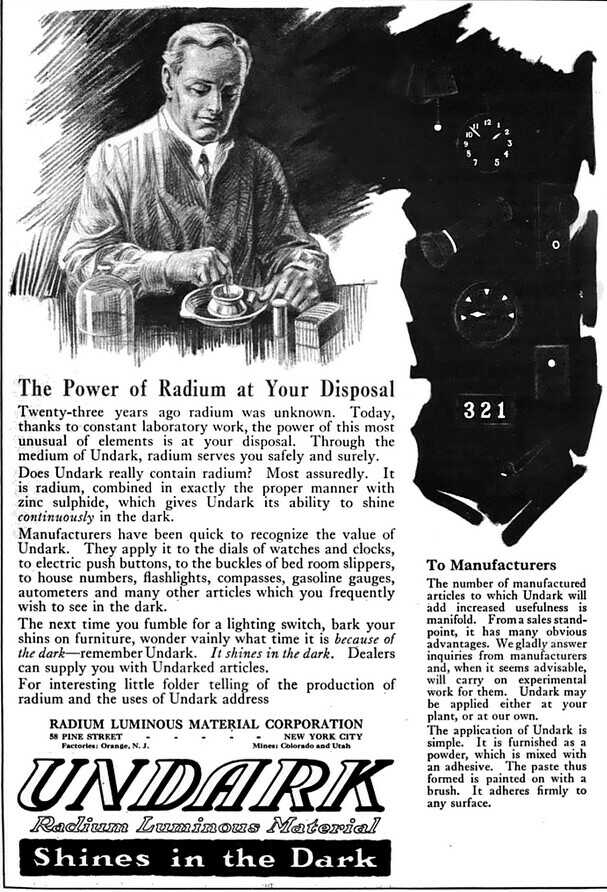

The Radium Girls were factory workers who from 1917 to 1926 hand-painted watch and clock dials with a glow-in-the-dark paint called Undark. The paint’s luminescence came from the radioactive silvery-white metal radium, then a recent and exciting discovery. U.S .Radium’s managers and scientists were aware of the paint’s dangers, but did not share that knowledge with the workers, who were encouraged to lick their brushes to bring them to a sharper point when applying the paint, ingesting tiny bits of radium. Some workers also painted their fingernails, hair and even teeth to make them glow at night. Within a few years, dozens of workers began showing signs of radiation poisoning.. They developed illnesses that included anemia, bone cancer, and necrosis of the jaw, known as “radium jaw”, which is as terrible as it sounds. By 1927, more than 50 had died.

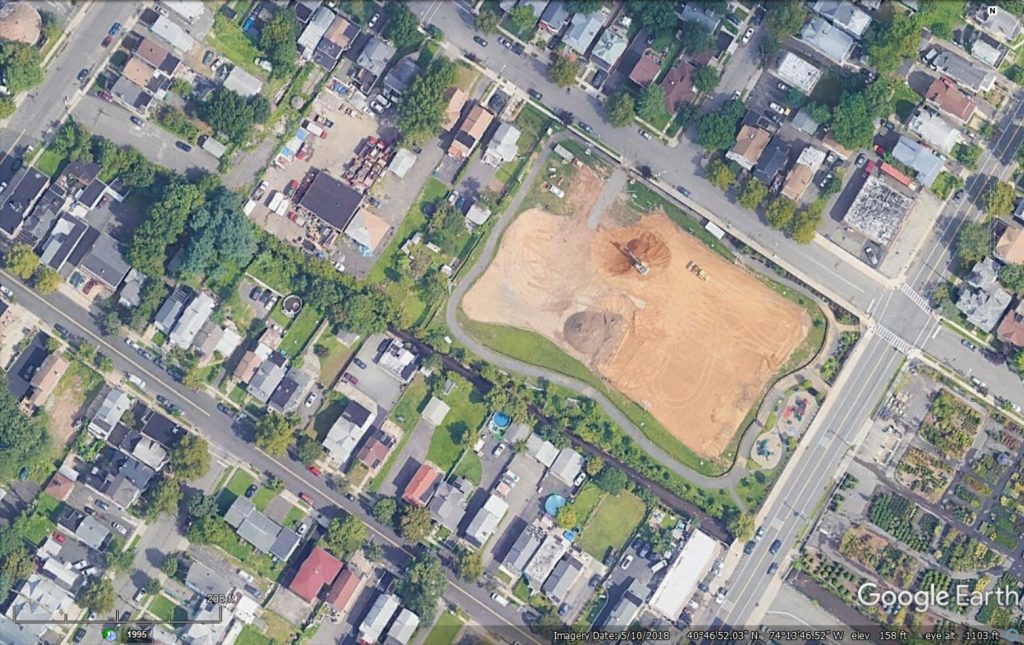

At the Orange, New Jersey plant where the women worked, the company also extracted radium from raw ore, by a process called radium crystallization. Approximately half a ton of dusty ore was processed each day, with the radioactive waste dumped both on-site and off.

A 1981 gamma-radiation survey by airplane found about 250 sites throughout Orange, West Orange, and South Orange, many of them residential, where radioactive waste had been dumped or used as construction fill. Sites in Montclair and Glen Ridge were also contaminated, earning them their own Superfund designations.

The basements and adjacent soil of houses built using contaminated fill had to be dug out and replaced, with the contaminated material shipped cross-country for burial in Utah. At the site in Orange, the top 22 feet of soil had to be removed.

U.S. Radium had two other dial-painting sites, one in Illinois and one in Connecticut, that also required remediation.

EPA findings and actions

“In 1979, EPA and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) initiated a program to identify and investigate locations within New Jersey where radium-processing activities had taken place. The former U.S .Radium Corporation processing plant was included in this program. In May 1981, EPA conducted an aerial gamma radiation survey covering approximately 12 square miles centered on the High and Alden Streets processing plant. This aerial survey located about 25 acres around the High and Alden Streets processing plant where elevated readings of gamma radiation were detected. This same survey identified areas of elevated gamma radiation in the nearby communities of Montclair, West Orange and Glen Ridge; the affected properties in these areas comprise two other Superfund sites, the Montclair/West Orange Radium site and the Glen Ridge Radium site.” — July 2011 EPA Review Report, full text available here.

Why I care

During the early 1950s, starting at about age 12, I played often at that site, No one knew about the contamination, not for thirty more years. Then on June 25, 1979, the New York Times published an article titled “Radiation Found at Site of Radium Plant Dating From the 1920’s“.

New Jersey’s humble Second River (to locals, simply ‘the brook’) flows alongside the site on its way east from First Mountain to join the Passaic River and Newark Bay. Who knows how much radioactive waste U.S Radium dumped into that little stream over the years? I played in that brook too, just a few blocks downstream, where minnows swam in the clear water.

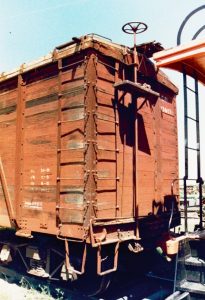

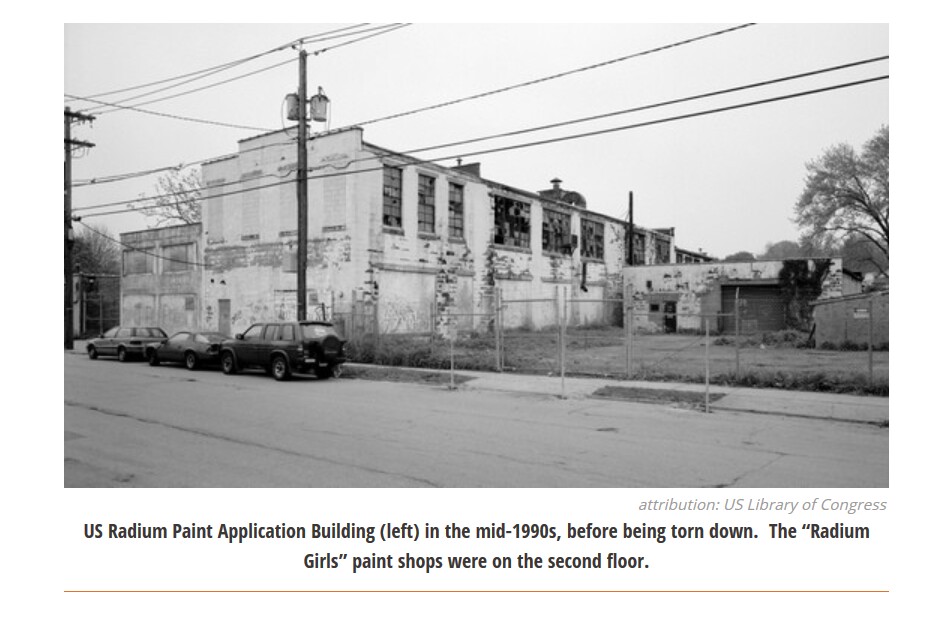

I played in the yard between the paint application building and the brook. Railroad tracks ran through the yard then, and there were usually one or two freight cars sitting there awaiting loading or unloading. Adjacent to the tracks were the too-grimy-to-play-on portable conveyor belts and sturdy bins of the neighboring Alden Coal Company. I enjoyed playing ‘railroad engineer’, climbing the rungs to the top of a car and twisting its parking-brake handwheel back and forth from one extreme to the other.

By then, the paint application building was occupied by Arpin Plastics, makers of the “Arpin 75 Special Repeating Water Pistol”. (I don’t know why anyone would buy a non-repeating water pistol .) They also made a Tommy gun, with greater water capacity and firepower. Weapons that didn’t pass inspection were tossed into a dumpster behind the building, from which they could be rescued and rehabilitated by anyone willing to put in a little effort.

Apparently I didn’t spend enough time at the site to develop any sort of radiation poisoning. Thanks for asking!